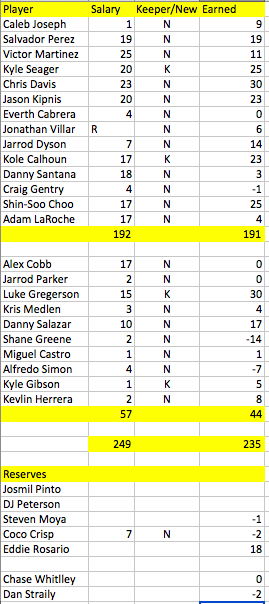

I bought the team you see on the left on April 5, 2015, to play in the American Dream League.

I bought the team you see on the left on April 5, 2015, to play in the American Dream League.

It is a keeper league, and I kept Kyle Seager, Kole Calhoun, Luke Gregerson and Kyle Gibson. I also kept Josmil Pinto as my first reserve pick, but he got hurt early in the season in the minors and was never called up.

Still, the other four did pretty well. Well enough to be, arguably, the best kept group in the league. That wasn’t clearly the case on auction day.

Alas, I made three costly errors in hitting on auction day: Victor Martinez (old and hurt and paid like he might repeat his extraordinary 2014 season), Adam LaRoche (got off to a hot start, but also old, and looked it as the season dragged on), and Danny Santana (young and spry but with massive holes in his swing and glove, thus spent most of the year in the minors).

These were all foreseeable outcomes, though none of the prices were crazy considering the players’ 2015 earnings. In any case, I preach it always but in this case I didn’t follow my own advice: Old guys, guys with notable flaws in their games, guys with potential health issues, have to be discounted. Otherwise, you don’t want them.

If you read my comments about Tout Wars, all I have to say here about pitching is, Ugh. I did it again. Kind of. The ADL is a 4×4 keeper league and it is known going in that the top pitchers will be kept or bid up. I priced the top guys aggressively, I thought, but they all went for premium prices. Shut out, unwilling to escalate too much, I got clever and decided to put my money on Alex Cobb, a top starter who was supposed to be back in six weeks. He didn’t come back, and was expensive bust No. 4.

Even so, in mid May I was in second place overall, and my staff was second in ERA and second in WHIP. My hitting was in terrible shape, because of slow starts by everyone. I tried to fix things on the waiver wire, but on April 20, our first week, I didn’t bid on Marco Estrada (who went for $4) and Shawn Tolleson (who went for $0). In the following weeks there wasn’t much pitching available, until Lance McCullers was called up.

I bid, but three teams bid more than $15 out of our $50 budgets. The winning team paid $19. I thought it was too expensive, until I saw McCullers pitch.

As, one by one, my high flying starters combusted, my team sank in the standings. Still, the team that finished last in the draft day standings was in fifth place as late as the penultimate week of the season.

Part of it was the ascension of Eddie Rosario and the resurrection of Shin-Shoo Choo (an old suspect guy who actually went at a discount). Some of it was adding Ben Revere at the trade deadline. I also had Kris Medlen come back in the second half, and picked up Josh Tomlin on waivers. They helped.

Another part was managing to top the league in Wins despite finishing next to last in ERA and fourth from last in WHIP. I had 26 wins from pitchers who had an ERA of more than 5.00 while they labored for my Bad K.

There are two lessons learned here.

1) Take flawed old players at a big discount or not at all. They may not fail, but the cost when they do should be less.

2) If going cheap in pitching, you have to have an ace. If you don’t have an ace you need a broader range of pitching support, which is going to cost more.

Looking at 2016, I have seven keepers max. How about?

Shin-Soo Choo 17

Chris Davis 23

Eddie Rosario 10

Jason Kipnis 20

Danny Salazar 10

Kelvin Herrera 2

Kris Medlen 3

On the Bubble

Salvador Perez 19

Caleb Joseph 1

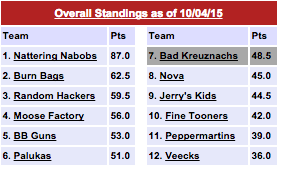

Last but not least, Walter Shapiro’s Nattering Nabobs kicked ass all season long. They moved into first place the third week of the season, and were never bested after, winning with a 35-year league record 87 points. Here’s the finals (yes, the Palukas passed me on the next to last day, dropping me into the second division):

the story of a guy’s fantasy team, don’t be misled. Walker crisscrosses the country, meeting fantasy experts, his opponents (often the same guys) and many of the players he rosters and gets their reactions to his team, his proposed and executed trades (I’ve long enjoyed David Ortiz stories, but Ortiz’s response to Walker asking if he would mind being traded for Alfonzo Soriano is indelible), their feelings about what sabermetricians say about the way they play, and his attempts—as his season careers out of control—to get managers and general managers to take advantage of the special information he has gleaned from watching the game so closely (and listening to his advisors), but all of this is informed by his larger themes and not the question of whether his team will win or not.

the story of a guy’s fantasy team, don’t be misled. Walker crisscrosses the country, meeting fantasy experts, his opponents (often the same guys) and many of the players he rosters and gets their reactions to his team, his proposed and executed trades (I’ve long enjoyed David Ortiz stories, but Ortiz’s response to Walker asking if he would mind being traded for Alfonzo Soriano is indelible), their feelings about what sabermetricians say about the way they play, and his attempts—as his season careers out of control—to get managers and general managers to take advantage of the special information he has gleaned from watching the game so closely (and listening to his advisors), but all of this is informed by his larger themes and not the question of whether his team will win or not.