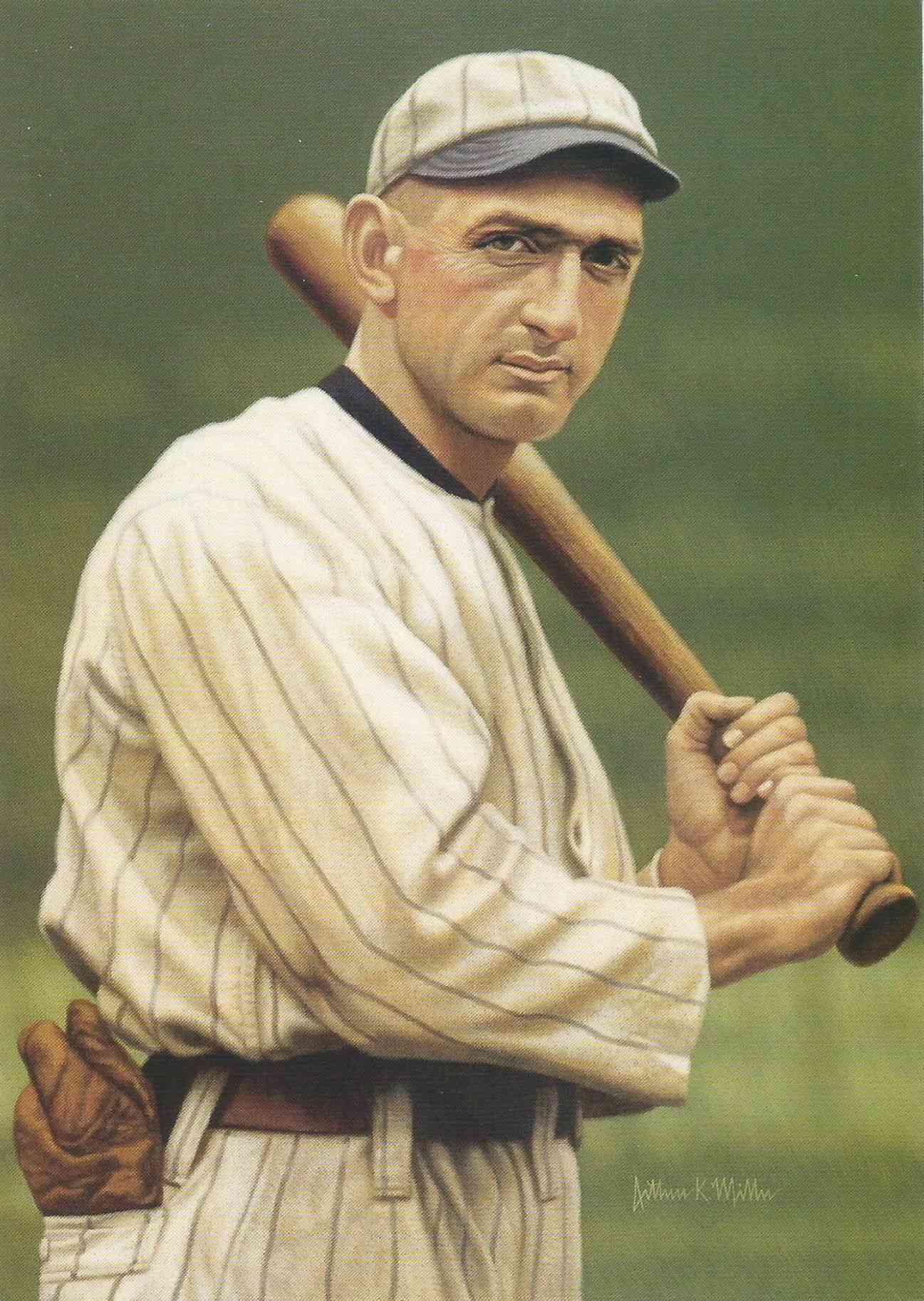

In this year’s Fantasy Baseball Guide 2020 (out now!), we received some bonus Picks and Pans from longtime contributor Kevin Cook and his son Cal. The Cooks imagined the Hall of Fame cases for Shoeless Joe Jackson, Pete Rose and Barry Bonds, written as Picks and Pans. I liked the idea so much I included them in the Guide’s editor’s letter. And I hoped that readers would come up with their own, which we would publish here.

That hasn’t happened, but I did hear from a reader named Steven McPherson, who knows a thing or two about the Eight Men Out. He wrote:

In regards the arguments made for Joe Jackson belonging in the Hall of Fame in the Letter from the Editor in The Fantasy Baseball Guide 2020. It states “he handled 30 chances without an error and threw out five baserunners.”

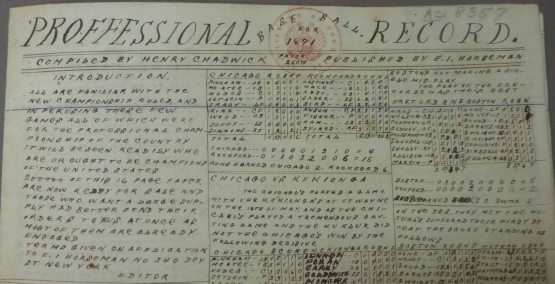

You are mistaken. He was credited with 16 put outs and one assist. The assist occurred in the sixth game when Jackson threw out Cincinnati second sack Morrie Rath at the plate in the fourth inning. The play-by-play in the Spaulding’s Official Base Ball Guide reads:

“Rath tried to score on Daubert’s short fly to Jackson. He was doubled at the plate as he slid into Schalk and knocked the little catcher over.”

In fact, a photo in the same publication suggests that Jackson made a poor throw up the first-base line, forcing Schalk to retrieve the poor throw and then dive back towards home plate into Rath’s flying spikes to make the tag. Great effort by the catcher who was not involved in the fixing of the Series.

BTW, the number of putouts by Jackson are meaningless anyway since, for example, in one inning he could misplay or misjudge five flyballs and still make three putouts.

I think Jackson probably did give his best effort in most of his plate appearances because he was, after all, playing for next year’s salary; however, it should not be overlooked that he did not run the bases particularly well: he was thrown out at least once trying to steal, doubled off at least twice after failing to tag up, and fell down at lest twice trying to advance on the bases.

Additionally, his public and legal versions of events changed radically so much so that in 1923 the Judge in his civil trial charged him with perjury.

In his 1920 Grand Jury testimony, he stated he had been promised $20,000 and received only $5,000 for his part in the fix.

FYI, you might enjoy the link below. There are also references to more updated research on this subject at this link.

Steve

PS- I agree with the takes on Barry Bonds and Pete Rose.

I know there are competing views about Shoeless Joe, so I forwarded Kevin Steve’s letter. He wrote back:

He’s right about the assists–that’ll teach me to accept a stat on Wikipedia. But putouts aren’t the same as chances handled. There were hits he fielded cleanly that he could have booted. I should certainly have been more careful about throwing out five baserunners, an awfully high number; I still think Joe still belongs in the Hall.

So there, an acceptance of a correction and a refutation. The debate will doubtless continue. Maybe it’s time for me to develop an opinion.