They’re available at Amazon, follow this link.

The softcover is $19.99. The Kindle edition is $9.99.

Answers to fantasy baseball questions (and much more) since 1996

They’re available at Amazon, follow this link.

The softcover is $19.99. The Kindle edition is $9.99.

Try Rotoman’s Fantasy Baseball Guide 2023 instead.

Supply chain, paper costs, inflation, whatever, the magazine’s publisher couldn’t see a way to break even on The Fantasy Baseball Guide 2023 and cancelled it.

So welcome to Rotoman’s Fantasy Baseball Guide 2023, where you’ll find player prices, projections, Rotoman’s Picks and Pans (hundreds of player profiles), a Rookie preview, and position by position cheat sheets. Online.

Free subscribers get the newsletters most days.

Paid subscribers get the newsletter, special newsletters, and access to the pricing and projections files on Google Sheets. Paid subscribers also get priority attention to their questions and suggestions for profiles. They also get extended access to back issues.

Paid annual subscribers also get free member access to PattonandCo.com, our favorite fantasy baseball discussion board. That’s a $36 value.

Have a question? Ask Rotoman!

Check out Rotoman’s Fantasy Baseball Guide 2023.

For 17 years I’ve played with a bunch of friends in a quirky keeper 5×5 (OBP) fantasy league called the XFL. We hold a $260 auction in the fall at First Pitch Arizona, keeping up to 15 players off the previous year’s rosters with a $5 increase (+$3 for players picked up before they had ML playing time). Then, in March, usually, we have a 17-round supplemental draft to round out our 40-man rosters.

Only this year, you know, we didn’t have that supplemental. We first put it off until April 20, and then as that date approached we collectively realized that it made no sense to spend time on something when conditions in the majors this year may be totally different, or that there may not even be a this year, so we postponed.

Which led to the idea of doing something. Anything. What that turned out to be, under the direction of Ron Shandler, was a draft of the major league players from 1982. I’m not sure why Ron chose ’82. I pushed for 1980, since that was the first year of our game and Dan Okrent’s piece about the Rotisserie League the following winter in Inside Sports magazine was called “The Year George Foster Wasn’t Worth $36.” But 1982 was fine, it was the first year I played the game, joining the Stardust League that Matthew Berry wrote about recently, in its second year.

There are things about a retrospective draft that are different than they are in a prospective draft. Our regular drafts and auctions before the season is played are shaped by our expectations–our projections–of what players may do, what chances there are that they will do more, or less, and how we put a price on that range of outcomes.

In a retro draft you know what a player has actually done, and you know the context in which he did it. That makes it fairly easy to come up with a value for each player and a ranking of player values. But it turns out that the math only gets you so far. Here’s why.

The Split: Many years ago, in the early ’90s, Les Leopold and I developed the idea that each player actually had two prices. One was his actual worth in the fantasy season just played (that’s his retro price), and his draft price, which was based on his projection and market expectations, what I call in The Guide The Big Price. We theorized that in a retrospective auction you would allocate 50 percent of your budget to pitching and 50 percent to hitting. This was something I tried to test for a long time, but there wasn’t much interest until everyone had to stay at home for months on end.

But alas, in preparing for this retro draft, it quickly became clear to me that allocating 50 percent to pitching didn’t solve all the problems. The one problem it did solve is that of pitcher injuries and unreliability, which are one and the same for the most part. Pitchers who stay healthy are reliable, but pitchers get hurt a lot. So while we discount pitching in our draft price, splitting our budgets about 65/35, spending half on pitching for half the points seemed like a good strategy.

But if you do that, I soon realized, you’re going to have to compete in all five pitching categories, and if you do that you’re going to bump into the fact that in a draft you can’t really load up your staff with aces. If you have the first pick and take Steve Carlton by the time you pick again all the other high strikeout, high wins starters will be gone. Drafts, obviously, are different than auctions, so once again we’re not testing the split.

Dumping: A draft is a linear playing field. The difference between the price of each successive pick is the same. But the value of the player pool is not the same. So, when you graph, say, the auction prices in a mixed league and compare it to the line of selections in a similarly configured mixed draft, you’ll see that the value of the first 50 or so picks is higher than the line, while after the third round most picks are under the line.

I prepared by running the available players through my pricing spreadsheet, adjusting for a 12 team mixed league. Absolute prices weren’t important for this exercise, it was a draft, but I tried to jigger the balance between the categories so that I didn’t overvalue low-ERA low-production pitchers. The danger of doing that is because you’re (I) using computed prices for the player’s season. When we’re ranking players prospectively, we don’t price their optimal performance but rather one that’s in the middle of the range of possibilities. Drafting retroactively, you know what Joe Niekro’s optimal performance was worth, but if the value of his ERA and Ratio outstrip Steve Carlton’s monster strikeouts and wins in your formula, are you putting together a roster that can win?

Maybe.

As it turns out, Brian Feldman (fantasybaseballauctioneer.com) led off with Carlton as the first pick. I had the wheel and took Andre Dawson with the 12th pick and Joaquin “Donde Esta Mi Cabeza” Andujar for some reason. Niekro was still there, higher on my sheet, but at that point my sheet was too big, too many columns, and I misread hits allowed for strikeouts in Andujar’s case and typed his name into the sheet. It was fine, they were close enough, but I had already deviated from my pricing.

At the next turn I took Dave Winfield and Goose Gossage, creating my own mini Yankees run which also set off a closer run. But I didn’t really mean to turn this into a play by play. There are a few other points about this exercise.

If you love baseball and play fantasy baseball this is potentially a great way to get together virtually with friends and spend some hours with a new way to play and talk about baseball. Some of us played fantasy baseball in 1982, some of us weren’t even born in 1982, but we all knew how great Robin Yount’s season was, how bad George Foster’s was. There was lots to talk about while selecting teams.

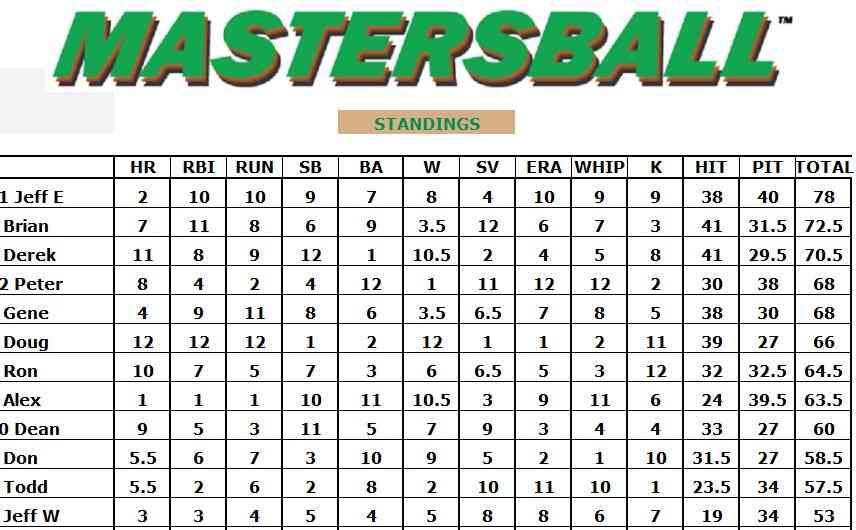

Zoom allowed us to see the excellent drafting spreadsheet that is part of the Mastersball.com package. A handful of us were also on camera, though the demands of keeping up with our lists meant we weren’t watching each other. The rest were on audio feeds, which was filled with banter and reminiscing.

The spreadsheet updated after each pick with revised standings, but we didn’t start checking that (Todd Zola was updating the sheet and he’d have to be asked to show that page) until more than halfway through. If I’d been paying attention to it earlier I would have seen that by not taking Ricky or Timmy or Willie my pursuit of steals was doomed, which would have changed some of my later picks as I vainly pursued the bottom of the steals pack and failed. This came to a head fairly deep in the draft when I selected Dickie Thon’s 37 saves and didn’t make a dent.

Position scarcity is something I didn’t think about in advance and though I was in the lead for a number of the first 20 rounds my team faded at the end. I don’t think that was caused by scarcity because when you know everyone’s value the math tells you the tradeoffs. If you take Gary Carter in the third you’re getting fewer stats than if you take Gary Ward, do you get that back later? You might, but that’s not a sure thing. A properly formed price list would have the exact 168 hitters with the positions necessary to fill 12 team rosters and prices rejiggered to reflect the fact that some of those catchers are of negative value when you price all players. They’re not negative valued when you have to pay for them, the prices have to change.

In the end, Jeff Erickson pulled out to a good lead in the last round, optimizing his categories. I failed at optimizing, wasting value by buying too much average, wasting money on steals, and having too low an ERA and WHIP. We’ll be playing again in a couple of weeks, Jeff picked the 1990 season, and you can be sure we’ll all be paying more attention, not necessarily balancing the categories, but more effectively managing the categories we dump. Or not.

Click here for the draft results.

The software is out now, full of projections, bid prices, expert league results, and prospect lists, in Windows software, Excel and Text Files.

The software is out now, full of projections, bid prices, expert league results, and prospect lists, in Windows software, Excel and Text Files.

It runs great on a Mac with Windows and Boot Camp, Parallels, or Fusion. If you want help preparing for your league, learn more about Patton $ Software and data by clicking here.

And joining Pattonandco.com, a lively discussion board about fantasy and real baseball, is free!

Rotoman!

I have the third overall pick in a 12 team league. Twofold question, I have a trade offer of my First Rounder for a 2nd, 4th and Sonny Gray. Is this good? The guy offering the trade is in the 7th slot. Second, if I keep the pick, Kershaw or Stanton? Assuming Trout and McCutchen go No. 1 & No. 2.

“Two Shades of Gray”

Dear Two Shades:

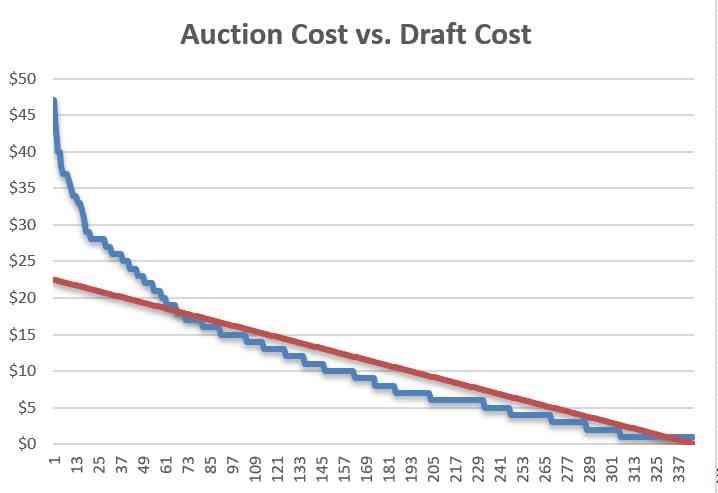

I have a simple chart to show you why you don’t want to trade your third pick for a 17th, 41st and Sony Gray.

Those are the prices, in descending order, for players in last year’s Tout Wars Mixed Auction. The things to notice here are the elegant curve of the line. On the left are the most expensive players, and on the right are the least expensive.

The 20 cheapest players cost $1. They’re that flat line to the far right. After that, the line moves pretty much straight up until you get to the 75th or so most expensive player, and then it starts getting steeper. By the time you get to the first 10 or so players, moving cheapest to most expensive, you’re clawing your way up a cliff.

This is the nature of the shallow mixed auction.

A shallow mixed draft is different. Each player taken in order is the best player available. So the price paid is one step down for each player taken. The line is a straight descending line, not unlike the auction values from about 75-336. But compare it to the auction line and you can see that the first 70 or 75 players are a draft’s bargains. And the earlier in the draft, the bigger the difference between the red line and the blue, which means the bigger the bargain.

I have to admit, Two Shades, from your description, I’m not sure what you’re ending up in this deal you’re talking about. But if I read it literally, you’re trading your first pick and ending up with two second picks and two fourth picks plus Sonny Gray. I hope that’s the deal, because then it is kind of close.

The marginal value of your five picks after the trade is $31, while you traded away $33 of marginal value. Plus you got Sonny Gray! To make up the diff!

But Sonny Gray’s ADP is 78 right now. That’s the magic point where the blue line crosses the red line. Ergo, Sonny Gray has no marginal value above his draft position. Getting him in trade doesn’t really help you at all.

So, not only are you trading more value to get less value, but you’re using up two more roster slots to do it. There is a recipe for such advice. Don’t do it.

Which takes us to part two of your question:

Kershaw or Stanton?

There is a good argument to be made for saying that Clayton Kershaw has the most value this year of any baseball player in the fantasy game. He’s coming off one of the best pitching seasons of all time, at a young age, during which he missed 15 percent of his starts because of injury. And now he’s healthy. Amazing.

So I think it makes sense to take Kershaw if he’s there.

But I also think you should hope that one of the guys ahead of you takes him and leaves you Trout or McCutchen or Goldschmidt.

If you take Kershaw early you’re going to have a heckuva time adding enough hitting to your mix. It can be done, but you’re going to be sacrificing your big hammer, that is the hitter people are willing to bid up. Whether that’s Trout, McCutchen, Goldschmidt or the other big name first round hitter who has special status because he plays middle infield, these are the guys who make up a big part of that value cliff on the auction chart.

Kershaw is in there, for sure, but somewhere there is another chart that shows that more pitchers will come out of the blue and earn $30 than hitters will. And not a few great pitchers fail at some point.

Which is why, with a Top 4 pick I’ll take a hitter. But Kershaw gets very viable after that.

Hi Rotoman –

Can you explain how prices sometimes do not coordinate with projections? For example below are your projections for Cashner and Wacha:

Cashner: 10 W, 3.53 ERA, 149 K, 1.24 WHIP

Wacha: 9 W, 3.45 ERA, 173 K, 1.16 WHIP

Yet you have Cashner at $16 and Wacha at $8.

Could the difference be perceived risk?

“Wacha Flaka Cashner”

Dear WFC:

In the Fantasy Guide, the projections are a starting point. They’re based on past performance rates regressed toward the mean, with some manual adjustments, scaled to a rough estimate of playing time (which is also regressed). The Projections are my attempt to describe a player using numbers. I hope that they give a sense how hittable a guy is, what sort of control he has, does he hit for average, can he run, that sort of thing.

The Big Prices in the Guide are my attempt to fix a guy’s value against the market. The prices are meant to be advice on who to buy and who to not buy. Essentially, I try to set the price on guys I expect to do well a buck or two higher than their “market” price. And guys I have concerns about, I set a buck or two lower.

It is important to note that the Prices add up to the budget for a 12-team AL or NL league with $260 budget per team. The reason to budget this way is because it helps you track the spending during the auction. If guys are going for more than the bid prices, you know that there are going to be bargains later. If guys are going for less? A bubble is born.

Now, let’s fast forward to March 15. That’s the day I posted the updated projections and prices here, for purchasers of the Guide. The adjusted projections were:

Cashner: 184 IP, 3.54 ERA, 10 W, 149 K, 1.14 WHIP

Wacha: 172 IP, 3.77 ERA, 11 W, 163 K, 1.24 WHIP

Now here’s the interesting part. The price for Cashner in 5×5 is $16. The price for Wacha is $15. But if you translate the above to dollar values, Cashner’s line is worth about $17, while Wacha’s is worth $8.

What happened?

Two things. As we hurtled toward the baseball season I learned that the market for Wacha is red hot. People consistently have him valued higher than Shelby Miller, which I think is a little wacky. It turns out that he tends to be going in the $16-$18 range in startup auctions. If I kept him at my pessimistic $8 price, it would look like a massive overpay when he went for twice that on draft day. But it isn’t really. The low end of the market for Wacha is $16, and I don’t want him at that.

Cashner, on the other hand, is a guy I want at $16. I mean, I’d rather have him at $14, and that’s been his average price this preseason, ranging from $13 to $15, but if I have to go $16 I’m okay with that.

The other thing I did was tinker with the projections to better reflect my perceptions about these two.

Wacha was a fastball/changeup guy last year. That’s it. An excellent fastball, a tough change, and early success, but it’s really hard to sustain a high level of success over multiple times through the lineup with just two pitches. No matter how good they are. My pessimism derives from the limited arsenal and the good chance that as major league scouts and hitters get repeated looks at him, there is going to be some payback.

The reason why most everyone thinks I’m wrong is because Wacha has added a curveball, which he threw a fair amount in his first start this year, and a cutter, which he didn’t throw much. It’s early, the pitches are new, and so there’s a lot we know. If he adds them effectively, he will become every bit the ace he looked like late last year. My bet is there is going to be some adjusting and he’s going to have some rough starts. So I think he’ll allow more hits and runs. We’ll see.

Cashner, on the other hand, is older, more experienced, has a more traditional fastball/slider/change repertoire already in place. I like him being at least as good as he was last year, when he earned $17.

The final word is that this process is one that consists of information, generated by the players that play, the press that follows them and tells the world what happened, and the numbers that describe what they did. This information is distilled by analysts as it comes in and added to both the projection, something of a description of average talent levels, and the market, which filters it all through the lens of risk and reward, which leads to bid values.

The whole process stops, for a few seconds at least, the moment the auctioneer says Sold! And then it starts all over again.

Mastersball.com’s Lawr Michaels tackles on-base percentage, as Tout Wars’ AL and NL leagues transition to the greatest stat ever! Um, to a better stat than Batting Average. Read it here.

Hi.

Many people asked this question when the Guide came out, so I wrote up a step-by-step guide here. And many more have asked me in the last couple of weeks.