I’ve now done three retro drafts, for 1982, 1990 and 1999. I wrote about the 1982 draft here, and have written about the 1990 and 1999 drafts at pattonandco.com, in the Stage Four thread.

I’ve finished in the Top 4 each time, but have yet to win one. I’ll be drafting next Wednesday night, taking apart the 1986 season. Fred Zinkie selected it because he won last week’s 1999 contest, jumping a mighty 11 points with his last round pick of Ryan Klesko.

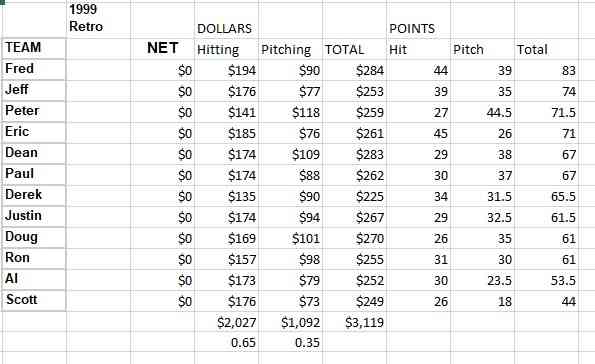

I took apart the draft a few different ways. First I looked at how many draft dollars each team bought in hitting and pitching, using my earnings values (which give positive value to the Top 108 pitchers and Top 168 hitters based on their 10 category stats).

Then I compared their earnings to their expected earnings for each draft slot (basically my earnings list sorted from highest to lowest), to see their NET value.

And I compared these things to their actual finish. Here are the data:

Looking at this, it doesn’t really pass the smell test. Dean earned more than Fred? How did Jeff finish so high while earning so little?

Someone over at pattonandco.com pointed out that Fred added Pedro Astacio, who I had valued at -$20 on the season. That appears to have cost him two points in ERA and WHIP combined, because of the way those categories were grouped, but gained him many more Wins and Strikeouts.

Someone else suggested that this indicated a problem with my pricing, but I don’t think that’s true in a general sense. But in a very specific sense the issue of who gets a positive value seems to have a lot of impact on pitcher prices. I wrote:

Doug led in ERA and was second in WHIP. I was second in ERA and third in WHIP. Dean was third in ERA and first in WHIP. Fred was first in strikeouts and fifth in ERA and WHIP. And the three of us are way ahead of the other nine teams, with Fred finishing just ahead of seven of them. That’s efficiency.

I think this shows not a problem with my pricing, but a problem with pricing in general. The dollar values work, but they then have to be applied to the right stats when you’re constructing your team. In other words, it’s not the meat it’s the motion.

But one issue to be aware of is that pitcher value very much depends on which 108 pitchers you value. The math will tell you one group, but as we can see, for a team in a particular position, a player like David Cone or Pedro Astacio will have real value and supplant one of the 70 inning relievers with a low ERA and Ratio that usually reside in the $1-$5 range.

So, if you go and reprice the actual pool, so that the worst pitcher is worth $1 and the 108 add up to $1092, the value of Pedro Martinez drops from $55 to $25. (I just did that.)

In the prospective leagues we usually price for, this phenomenon drives up the value of the best pitchers, but when we know what the stats are going to add up to it seems to do the opposite. Here’s how the Retro earnings looks with the pitching pool repriced.

This doesn’t really make sense to me logically but eyeballing the Dollar totals in this chart makes more sense to me than the earlier one.

Note: I also adjusted the hitters in a similar way after noticing that the total wasn’t adding up to $3120. These results look more like what I would have expected, demonstrating that in a retro draft to get good prices you need to know which players will be selected.